The Reformed Churches by their recognition of the household of the believer as a unit in their fellowship were shut in to what they looked upon as no bondage. Their views on the membership of the Visible Church, as we have seen, found a place in the constituency for the children of those who were saints by profession. These were looked upon as being in virtue of their birth in believing homes entitled to be acknowledged as outwardly sanctified or specially set apart by the Head of the Church to enjoy external privileges in His house, and so laid under a corresponding obligation to take His yoke upon their shoulders. They were regarded as part and parcel of the holy nation of New Testament times; and therefore it was looked upon as a warranted thing that they should have the seal of the covenant and at the least a probationary place in the ranks of the organized Christian Kingdom. Because they were federally holy they were to be recognized as being so in Baptism.

Such a doctrine as this laid the obligation upon the Church to see to the due training of its infant membership. In this connection the task was looked upon as a twofold one. It left room for distinct yet concurrent action on the part of the Church and the Home. There was a duty recognized as lying upon parents to teach and to train their children. They were to look upon them as not only their own children, for whose highest good they were naturally bound to labor and to pray, they were also to regard them, since the Church of the Living God had taken them as her own, as the children of the King’s daughter, the daughter of the King of Kings. This being so, it was but right and seemly that the children of such a mother should have an upbringing in keeping with their privileged rank. Their parents then, as their natural guardians, were to bring them up and train them, bearing in mind the need that their children, owned in Baptism as having a place in the Church of God, should be taught and guided and molded by every means within their reach, so that they shall be shut in to Christ as their Savior, and that they may take Him as their own.

The obligation lying upon the Church is the other side of the task that has to be carried out. The parents are not relieved of their natural obligation. They have their children given back to them as their proper guardians in Baptism, and they are to bring them up as the children of the King’s daughter. She whose adopted and acknowledged children they are has the task and burden laid upon her of praying, and not only praying but also laboring for them. She is to see to the due training of those that she has accepted as her own. In seeking to carry out the obligation that she thus felt to be laid upon her, the Church of the Reformation in different lands showed great diligence in providing manuals of instruction which took the form of Catechisms. Thus, for example, in the Acts of the Synod of Dort the obligation to teach the young people is recognized. ‘That the Christian youth from their tender years may be carefully trained in the fundamental truths of true religion and imbued with true piety this threefold method of Catechizing ought to be taken, at home by their parents, at school by their teachers, and in Church life by their pastors, elders and readers or sick-visitors, etc.’

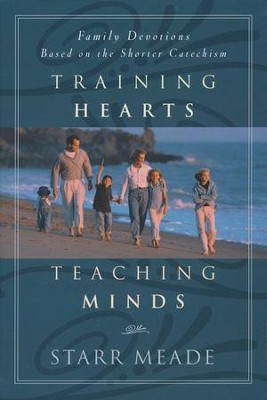

Notable among the Reformed Catechisms were Calvin’s Geneva Catechism, the Heidelberg Catechism and the Westminster Shorter Catechism. The aim of the Church in the use of these was to teach the truth of God’s Word to her rising membership. These handbooks were provided for parents and teachers as well as for their charges. For one of the things that the Reformed Church tried to secure was to have a well-instructed constituency. The Jesuits said that if they had a child for the first seven years of his life they did not fear who should have him afterwards. This was a game at which two could play. And in their palmy days the Reformed Churches were not behindhand in looking after the young of the flock. They aimed at raising up within their borders successors who would range themselves under the banner of the Gospel and who would seek to perpetuate such a goodly order. It was looked upon as part of the ordinary work of the ministry that they should see well to the state of their flocks in respect of godly nurture and instruction. And the outcome of such a program was that – at least in the flourishing times of our Reformed Church in Scotland – in the homes of the people household worship morning and evening, with the acknowledgment of God at every meal, was the recognized practice of the land. Now worship that called for the reading of the Word of God called for and was fitted to produce an educated community which sought out and sought after the Word of God written, and which strove to bring up its children from the dawn of life in the knowledge of that Word and of the Church’s Confession and Catechisms.

Such a catechetical method in pedagogy as found favor among our Reforming fathers was one that cut right across the modern practice in this department which throws the reins loose and lets the horse please itself. Go-as-you-please teachers allow the wishes and the whims of their scholars to map out for them their course. It was the fashion of older days that the dog should wag its own tail. The modern inversion that the tail should wag the dog hardly looks a natural or a reasonable kind of thing.

When objection is taken to the catechetic mode of instruction by way of question and answer, a mode which calls for the learning by heart of an answer that has been carefully drawn up to convey a maximum of sound knowledge in a memorable form, it is said that this sort of instruction is too one-sidedly intellectual, that it overloads the memory, that it shoots over the head of the scholar, that it does not reach the end of opening up the truth by reason of the very abstruseness and detachment of its matter and method. Those who take such a line of criticism forget a thing or two that it would be well for them to bear in mind.

For one thing, the use of catechetical manuals supplies the parent and the teacher with material that a competent teacher will put to a wise use. He will open up the real content of the answers that the pupil has committed to memory. The instructor may have himself learned these words in his youth and assimilated them only in part. He may now find out that in the endeavor to teach another the thing opens up to himself better than it ever did before, and he may meet with more success in his work than the teachers, that he himself had, met with in his own case when he was young. Now that he is come to maturity he is better able to grasp the meaning of the words that he learned in his early days. It was good for him to have such words stored up in his memory. It trained and exercised that faculty. And now that he sees their meaning better than he once did, he will seek to bring home to his pupils’ understanding what he had himself in his youth failed to grasp.

Then it is a well-known fact that memory is more impressionable and retentive in early years than it is in later life. And while the acquisitive powers of memory are at their best it is possible by exercising them well to strengthen and develop them and furnish the young with what will be a life-time treasure. At the same time the powers of the understanding come to their maturity and strength in later years when the powers of memory have passed their zenith. In the years when memory is at its best the powers of the understanding, though not yet mature, are already at work, so that there should be not only drill in memory work but exposition and explanation to open up the meaning of the lessons taught. One does not need to delay until maturer years to come to an appreciation of truth that is learned by heart.

Then again in so far as the powers of the understanding come later to full functioning, it is well that the millstones of consideration and reflection as they go round should have something to grind. And here comes in a special value that attaches to what has been learned by heart yet has not been quite grasped in younger years. In such a case when the stores of memory give them something to go on with, the millstones do not grind each the other into hard grit. They have choice wheat to work upon. What has been learned at the outset of life is thus fitted to come into its own, and the matured powers of reason and of understanding do not work in vacuo. The adult mind has something provided for it which gives food for thought.

In the light of these things we see that there was wisdom and sound psychology in the method adopted by our fathers. They sought to indoctrinate their children in the knowledge and faith of the Gospel; and, as they did so, they tried to impress upon them the truth that no parrot knowledge of sound words will suffice. It will suffice no more than the parrot repetition of forms of prayer can serve as a substitute for true prayer, for prayer is offered to Him Who is not only its Hearer, but the Searcher of the heart. There is a fault in the method of instruction when it only heaps up in the memory what may be so much dead lumber, or is one-sidedly intellectual. The teacher who seeks to teach indeed will not only store the memory with what is valuable; he will seek to open up the meaning of the truth that he is trying to teach, so as to make it as clear and as simple as possible. And to make it at once memorable and interesting he will use the method of illustration, call in the legitimate resources of feeling and of fancy, and so enlist the sympathies and rouse an interest in what is taught. The method of learning by rote is one that has been justified by its ultimate results. It bred among us generations who were schooled in the knowledge of Christian doctrine, and who had a keen edge on their discernment. They could tell readily when the teaching that they heard went out of the right way, for their understanding of the truth was disciplined.

The emphasis that our Reformers and their loyal successors laid upon the godly upbringing of the young is registered, not only in the watchful discipline of the Church, which guarded purity of life and the sanctity of the home as the nursery of the Church; it came out also in the number of helps that saw the light by way not only of Catechisms, but of Commentaries upon them, and the systematic habit of using them. The survival of the old order is within the memory of men yet alive who saw ministerial catechizing of the households of the flock as part of the regular routine of the life of old school Presbyterian congregations. Indeed, happily, it is not yet a thing altogether of the past. For such diets of catechizing there used to be careful preparation, and when they came they were not shunned but welcomed. Such a devotion to the study of Christian truth could not fail to exercise an influence direct or reflex on the tone of the community. In particular, the homes that were accustomed to the old order of Reformed Scotland, for it is of this country that we speak at present, used to have a fireside Sabbath School, the memory of whose lessons is a bright spot in the record of the years that are gone. When Sabbath Schools were begun it was not meant that they should take the place of home teaching and training. And few would venture to say that the measure in which they have served to oust these and to relieve parents of a sense of duty in regard to the teaching of their households is an index to improved conditions in the life of the Church. The old order produced generations of instructed hearers. And if it might happen that at times there was more knowledge of the letter of Christian truth than there was practical experience and illustration of its power, the blame lay, not with the success of the endeavors to teach, but with the failure of those endeavors. In such instances they did not reach their intended goal. The system did not do everything that it set out to do. But it did much; and its outcome in the life of the Church and of the commonwealth tells of what good came of it. There is like good that is still to be looked for when the blessing of God crowns loyalty to the claims of household godliness. Such godliness shows itself as of old in the instruction of the children, and in striving to bring home to each of them in turn his personal responsibility and his need of a saving knowledge of the Gospel of our salvation, and of Christ as our Savior and Lord.

For the first fruit borne by the application of the Reformed presentation of Christian truth to the domestic institute we may look to the record of those regions and eras when the application was most faithfully made. If, to the eyes of our Scottish Reformed, Geneva was in Calvin’s day the most perfect school of Christ that was to be seen anywhere, one has only to turn to the moral and spiritual elevation of the godly homes of Huguenot France, of the confessing Netherlands, of Protestant and Puritan England and New England, and of this Covenanted country to see what a benign and blessed, what an educative and elevating and evangelizing influence this application put forth in the communities that came under its sway. We might take two concrete instances to which we may appeal in illustration, and they are but two out of a countless multitude. Who that has read about the family life of Philip Henry in Puritan England or, as it comes out in Domestic Portraiture of Leigh Richmond, in the hey-day of a reviving Evangel in England over a century ago, can fail to see the beauty of the lives that bore witness to the blessing of God as it crowned the faithful diligence of parents whose resolve was that, as for them and for their house, they would serve the Lord? Let men but see such homes multiplied, with their influence telling on the commonwealth at large, and it would be evident how beneficent the influence was that was wielded by the household godliness which made the home the happiest place on earth. This experiment has been made on a wide scale already. Let it be made on a wider scale still, and the care that is devoted to the godly upbringing of the young will reflect its working and its power in the life of Church and State both. We have said already, and before we conclude we may repeat it, that we do not make any exclusive claim by way of monopoly. We venture merely to indicate what a close and loyal adherence to the Reformed ideal of the visible Church and its concrete application to the home as a unit in that larger fellowship has done. This is an index to its potency. And the diligence that it calls for in teaching the Word of God, and in showing the beauty of a Christian life lived in the unrestrained freedom of home conditions, is an expenditure of energy that will richly repay itself. The sedulous care that our Reforming fathers called for in the oversight of the young shows how their eye with statesman-like prescience was directed to the future. They were not content with the past whose record was closed, nor with the present with its limited measure of success. They looked forward to the days that were yet to be for the full answer to the prayer that the Lord has taught His disciples to offer that the kingdom of God may come. With its coming the face of the world will be changed; and a godless and selfish and unbelieving world needs, if it is to be set right, that it should be turned upside down. The natural institution of the family taken up and blessed in the kingdom of God will be a mighty instrument for achieving this end.