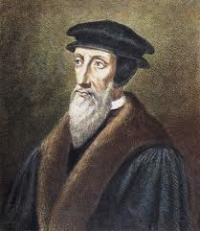

The following selection by John Calvin was taken from book 3, chapter 11 of The Institutes of The Christian Religion, translated into English by Henry Beveridge, 1863. This electronic edition is in the public domain and may be freely copied and distributed.

1. I trust I have now sufficiently shown how man’s only resource for escaping from the curse of the law, and recovering salvation, lies in faith; and also what the nature of faith is, what the benefits which it confers, and the fruits which it produces. The whole may be thus summed up: Christ given to us by the kindness of God is apprehended and possessed by faith, by means of which we obtain in particular a twofold benefit; first, being reconciled by the righteousness of Christ, God becomes, instead of a judge, an indulgent Father; and, secondly, being sanctified by his Spirit, we aspire to integrity and purity of life. This second benefit, viz., regeneration, appears to have been already sufficiently discussed. On the other hand, the subject of justification was discussed more cursorily, because it seemed of more consequence first to explain that the faith by which alone, through the mercy of God, we obtain free justification, is not destitute of good works; and also to show the true nature of these good works on which this question partly turns. The doctrine of Justification is now to be fully discussed, and discussed under the conviction, that as it is the principal ground on which religion must be supported, so it requires greater care and attention. For unless you understand first of all what your position is before God, and what the judgment which he passes upon you, you have no foundation on which your salvation can be laid, or on which piety towards God can be reared. The necessity of thoroughly understanding this subject will become more apparent as we proceed with it.

2. Lest we should stumble at the very threshold, (this we should do were we to begin the discussion without knowing what the subject is,) let us first explain the meaning of the expressions, To be justified in the sight of God, to be Justified by faith or by works. A man is said to be justified in the sight of God when in the judgment of God he is deemed righteous, and is accepted on account of his righteousness; for as iniquity is abominable to God, so neither can the sinner find grace in his sight, so far as he is and so long as he is regarded as a sinner. Hence, wherever sin is, there also are the wrath and vengeance of God. He, on the other hand, is justified who is regarded not as a sinner, but as righteous, and as such stands acquitted at the judgment-seat of God, where all sinners are condemned. As an innocent man, when charged before an impartial judge, who decides according to his innocence, is said to be justified by the judge, as a man is said to be justified by God when, removed from the catalogue of sinners, he has God as the witness and assertor of his righteousness. In the same manner, a man will be said to be justified by works, if in his life there can be found a purity and holiness which merits an attestation of righteousness at the throne of God, or if by the perfection of his works he can answer and satisfy the divine justice. On the contrary, a man will be justified by faith when, excluded from the righteousness of works, he by faith lays hold of the righteousness of Christ, and clothed in it appears in the sight of God not as a sinner, but as righteous. Thus we simply interpret justification, as the acceptance with which God receives us into his favor as if we were righteous; and we say that this justification consists in the forgiveness of sins and the imputation of the righteousness of Christ, (see sec. 21 and 23.)

3. In confirmation of this there are many clear passages of Scripture. First, it cannot be denied that this is the proper and most usual signification of the term. But as it were too tedious to collect all the passages, and compare them with each other, let it suffice to have called the reader’s attention to the fact: he will easily convince himself of its truth. I will only mention a few passages in which the justification of which we speak is expressly handled. First, when Luke relates that all the people that heard Christ “justified God,” (Luke 7: 29,) and when Christ declares, that “Wisdom is justified of all her children,” (Luke 7: 35,) Luke means not that they conferred righteousness which always dwells in perfection with God, although the whole world should attempt to wrest it from him, nor does Christ mean that the doctrine of salvation is made just: this it is in its own nature; but both modes of expression are equivalent to attributing due praise to God and his doctrine. On the other hand, when Christ upbraids the Pharisees for justifying themselves, (Luke 16: 15,) he means not that they acquired righteousness by acting properly, but that they ambitiously courted a reputation for righteousness of which they were destitute. Those acquainted with Hebrew understand the meaning better: for in that language the name of wicked is given not only to those who are conscious of wickedness, but to those who receive sentence of condemnation. Thus, when Bathsheba says, “I and my son Solomon shall be counted offenders,” she does not acknowledge a crime, but complains that she and her son will be exposed to the disgrace of being numbered among reprobates and criminals, (1 Kings 1: 21.) It is, indeed, plain from the context, that the term even in Latin must be thus understood, viz., relatively, and does not denote any quality. In regard to the use of the term with reference to the present subject, when Paul speaks of the Scripture, “foreseeing that God would justify the heathen through faith,” (Gal. 3: 8,) what other meaning can you give it than that God imputes righteousness by faith? Again, when he says, “that he (God) might be just, and the justifier of him who believeth in Jesus,” (Rom. 3: 26,) what can the meaning be, if not that God, in consideration of their faith, frees them from the condemnation which their wickedness deserves? This appears still more plainly at the conclusion, when he exclaims, “Who shall lay any thing to the charge of God’s elect? It is God that justifieth. Who is he that condemneth? It is Christ that died, yea rather, that is risen again, who is even at the right hand of God, who also maketh intercession for us, (Rom. 8: 33, 34.) For it is just as if he had said, Who shall accuse those whom God has acquitted? Who shall condemn those for whom Christ pleads? To justify therefore, is nothing else than to acquit from the charge of guilt, as if innocence were proved. Hence, when God justifies us through the intercession of Christ, he does not acquit us on a proof of our own innocence, but by an imputation of righteousness, so that though not righteous in ourselves, we are deemed righteous in Christ. Thus it is said, in Paul’s discourse in the Acts, “Through this man is preached unto you the forgiveness of sins; and by him all that believe are justified from all things from which ye could not be justified by the law of Moses,” (Acts 13: 38, 39.) You see that after remission of sins justification is set down by way of explanation; you see plainly that it is used for acquittal; you see how it cannot be obtained by the works of the law; you see that it is entirely through the interposition of Christ; you see that it is obtained by faith; you see, in fine, that satisfaction intervenes, since it is said that we are justified from our sins by Christ. Thus when the publican is said to have gone down to his house “justified,” (Luke 18: 14,) it cannot be held that he obtained this justification by any merit of works. All that is said is, that after obtaining the pardon of sins he was regarded in the sight of God as righteous. He was justified, therefore, not by any approval of works, but by gratuitous acquittal on the part of God. Hence Ambrose elegantly terms confession of sins “legal justification,” (Ambrose on Psalm 118 Serm. 10).

4. Without saying more about the term, we shall have no doubt as to the thing meant if we attend to the description which is given of it. For Paul certainly designates justification by the term acceptance, when he says to the Ephesians, “Having predestinated us unto the adoption of children by Jesus Christ to himself, according to the good pleasure of his will, to the praise of the glory of his grace, wherein he has made us accepted in the Beloved,” (Eph. 1: 5, 6.) His meaning is the very same as where he elsewhere says, “being justified freely by his grace,” (Rom. 3: 24.) In the fourth chapter of the Epistle to the Romans, he first terms it the imputation of righteousness, and hesitates not to place it in forgiveness of sins: “Even as David also describeth the blessedness of the man unto whom God imputeth righteousness without works, saying, Blessed are they whose iniquities are forgiven,” &c., (Rom. 4: 6-8.) There, indeed, he is not speaking of a part of justification, but of the whole. He declares, moreover, that a definition of it was given by David, when he pronounced him blessed who has obtained the free pardon of his sins. Whence it appears that this righteousness of which he speaks is simply opposed to judicial guilt. But the most satisfactory passage on this subject is that in which he declares the sum of the Gospel message to be reconciliation to God, who is pleased, through Christ, to receive us into favor by not imputing our sins, (2 Cor. 5: 18-21.) Let my readers carefully weigh the whole context. For Paul shortly after adding, by way of explanation, in order to designate the mode of reconciliation, that Christ who knew no sin was made sin for us, undoubtedly understands by reconciliation nothing else than justification. Nor, indeed, could it be said, as he elsewhere does, that we are made righteous “by the obedience” of Christ, (Rom. 5: 19,) were it not that we are deemed righteous in the sight of God in him and not in ourselves.

5. But as Osiander has introduced a kind of monstrosity termed essential righteousness, by which, although he designed not to abolish free righteousness, he involves it in darkness, and by that darkness deprives pious minds of a serious sense of divine grace; before I pass to other matters, it may be proper to refute this delirious dream. And, first, the whole speculation is mere empty curiosity. He indeed, heaps together many passages of scripture showing that Christ is one with us, and we likewise one with him, a point which needs no proof; but he entangles himself by not attending to the bond of this unity. The explanation of all difficulties is easy to us, who hold that we are united to Christ by the secret agency of his Spirit, but he had formed some idea akin to that of the Manichees, desiring to transfuse the divine essence into men. Hence his other notion, that Adam was formed in the image of God, because even before the fall Christ was destined to be the model of human nature. But as I study brevity, I will confine myself to the matter in hand. He says, that we are one with Christ. This we admit, but still we deny that the essence of Christ is confounded with ours. Then we say that he absurdly endeavors to support his delusions by means of this principle: that Christ is our righteousness, because he is the eternal God, the fountain of righteousness, the very righteousness of God. My readers will pardon me for now only touching on matters which method requires me to defer to another place. But although he pretends that, by the term essential righteousness, he merely means to oppose the sentiment that we are reputed righteous on account of Christ, he however clearly shows, that not contented with that righteousness, which was procured for us by the obedience and sacrificial death of Christ, he maintains that we are substantially righteous in God by an infused essence as well as quality. For this is the reason why he so vehemently contends that not only Christ but the Father and the Spirit dwell in us. The fact I admit to be true, but still I maintain it is wrested by him. He ought to have attended to the mode of dwelling, viz., that the Father and the Spirit are in Christ; and as in him the fulness of the Godhead dwells, so in him we possess God entire. Hence, whatever he says separately concerning the Father and the Spirit, has no other tendency than to lead away the simple from Christ. Then he introduces a substantial mixture, by which God, transfusing himself into us, makes us as it were a part of himself. Our being made one with Christ by the agency of the Spirit, he being the head and we the members, he regards as almost nothing unless his essence is mingled with us. But, as I have said, in the case of the Father and the Spirit, he more clearly betrays his views, namely, that we are not justified by the mere grace of the Mediator, and that righteousness is not simply or entirely offered to us in his person, but that we are made partakers of divine righteousness when God is essentially united to us.

6. Had he only said, that Christ by justifying us becomes ours by an essential union, and that he is our head not only in so far as he is man, but that as the essence of the divine nature is diffused into us, he might indulge his dreams with less harm, and, perhaps, it were less necessary to contest the matter with him; but since this principle is like a cuttle-fish, which, by the ejection of dark and inky blood, conceals its many tails, if we would not knowingly and willingly allow ourselves to be robbed of that righteousness which alone gives us full assurance of our salvation, we must strenuously resist. For, in the whole of this discussion, the noun righteousness and the verb to justify, are extended by Osiander to two parts; to be justified being not only to be reconciled to God by a free pardon, but also to be made just; and righteousness being not a free imputation, but the holiness and integrity which the divine essence dwelling in us inspires. And he vehemently asserts (see sec. 8) that Christ is himself our righteousness, not in so far as he, by expiating sins, appeased the Father, but because he is the eternal God and life. To prove the first point, viz., that God justifies not only by pardoning but by regenerating, he asks, whether he leaves those whom he justifies as they were by nature, making no change upon their vices? The answer is very easy: as Christ cannot be divided into parts, so the two things, justification and sanctification, which we perceive to be united together in him, are inseparable. Whomsoever, therefore, God receives into his favor, he presents with the Spirit of adoption, whose agency forms them anew into his image. But if the brightness of the sun cannot be separated from its heat, are we therefore to say, that the earth is warmed by light and illumined by heat? Nothing can be more apposite to the matter in hand than this simile. The sun by its heat quickens and fertilizes the earth; by its rays enlightens and illumines it. Here is a mutual and undivided connection, and yet reason itself prohibits us from transferring the peculiar properties of the one to the other. In the confusion of a twofold grace, which Osiander obtrudes upon us, there is a similar absurdity. Because those whom God freely regards as righteous, he in fact renews to the cultivation of righteousness, Osiander confounds that free acceptance with this gift of regeneration, and contends that they are one and the same. But Scriptures while combining both, classes them separately, that it may the better display the manifold grace of God. Nor is Paul’s statement superfluous, that Christ is made unto us “righteousness and sanctification,” (1 Cor. 1: 30.) And whenever he argues from the salvation procured for us, from the paternal love of God and the grace of Christ, that we are called to purity and holiness, he plainly intimates, that to be justified is something else than to be made new creatures. Osiander on coming to Scripture corrupts every passage which he quotes. Thus when Paul says, “to him that worketh not, but believeth on him that justifieth the ungodly, his faith is counted for righteousness,” he expounds justifying as making just. With the same rashness he perverts the whole of the fourth chapter to the Romans. He hesitates not to give a similar gloss to the passage which I lately quoted, “Who shall lay any thing to the charge of God’s elect? It is God that justifieth.” Here it is plain that guilt and acquittal simply are considered, and that the Apostle’s meaning depends on the antithesis. Therefore his futility is detected both in his argument and his quotations for support from Scripture. He is not a whit sounder in discussing the term righteousness, when it is said, that faith was imputed to Abraham for righteousness after he had embraced Christ, (who is the righteousness of Gad and God himself) and was distinguished by excellent virtues. Hence it appears that two things which are perfect are viciously converted by him into one which is corrupt. For the righteousness which is there mentioned pertains not to the whole course of life; or rather, the Spirit testifies, that though Abraham greatly excelled in virtue, and by long perseverance in it had made so much progress, the only way in which he pleased God was by receiving the grace which was offered by the promise, in faith. From this it follows, that, as Paul justly maintains, there is no room for works in justification.

7. When he objects that the power of justifying exists not in faith, considered in itself, but only as receiving Christ, I willingly admit it. For did faith justify of itself, or (as it is expressed) by its own intrinsic virtue, as it is always weak and imperfect, its efficacy would be partial, and thus our righteousness being maimed would give us only a portion of salvation. We indeed imagine nothing of the kind, but say, that, properly speaking, God alone justifies. The same thing we likewise transfer to Christ, because he was given to us for righteousness; while we compare faith to a kind of vessel, because we are incapable of receiving Christ, unless we are emptied and come with open mouth to receive his grace. Hence it follows, that we do not withdraw the power of justifying from Christ, when we hold that, previous to his righteousness, he himself is received by faith. Still, however, I admit not the tortuous figure of the sophist, that faith is Christ; as if a vessel of clay were a treasure, because gold is deposited in it. And yet this is no reason why faith, though in itself of no dignity or value, should not justify us by giving Christ; Just as such a vessel filled with coin may give wealth. I say, therefore, that faith, which is only the instrument for receiving justification, is ignorantly confounded with Christ, who is the material cause, as well as the author and minister of this great blessing. This disposes of the difficulty, viz., how the term faith is to be understood when treating of justification.

8. Osiander goes still farther in regard to the mode of receiving Christ, holding, that by the ministry of the external word the internal word is received; that he may thus lead us away from the priesthood of Christ, and his office of Mediator, to his eternal divinity. We, indeed, do not divide Christ, but hold that he who, reconciling us to God in his flesh, bestowed righteousness upon us, is the eternal Word of God; and that he could not perform the office of Mediator, nor acquire righteousness for us, if he were not the eternal God. Osiander will have it, that as Christ is God and man, he was made our righteousness in respect not of his human but of his divine nature. But if this is a peculiar property of the Godhead, it will not be peculiar to Christ, but common to him with the Father and the Spirit, since their righteousness is one and the same. Thus it would be incongruous to say, that that which existed naturally from eternity was made ours. But granting that God was made unto us righteousness, what are we to make of Paul’s interposed statement, that he was so made by God? This certainly is peculiar to the office of mediator, for although he contains in himself the divine nature, yet he receives his own proper title, that he may be distinguished from the Father and the Spirit. But he makes a ridiculous boast of a single passage of Jeremiah, in which it is said, that Jehovah will be our righteousness, (Jer. 23: 6; 33: 16.) But all he can extract from this is, that Christ, who is our righteousness, was God manifest in the flesh. We have elsewhere quoted from Paul’s discourse, that God purchased the Church with his own blood, (Acts 20: 28.) Were any one to infer from this that the blood by which sins were expiated was divine, and of a divine nature, who could endure so foul a heresy? But Osiander, thinking that he has gained the whole cause by this childish cavil, swells, exults, and stuffs whole pages with his bombast, whereas the solution is simple and obvious, viz., that Jehovah, when made of the seed of David, was indeed to be the righteousness of believers, but in what sense Isaiah declares, “By his knowledge shall my righteous servant justify many,” (Isa. 53: 11.) Let us observe that it is the Father who speaks. He attributes the office of justifying to the Son, and adds the reason, – because he is “righteous.” He places the method, or medium, (as it is called,) in the doctrine by which Christ is known. For the word “da’at” is more properly to be understood in a passive sense. Hence I infer, first, that Christ was made righteousness when he assumed the form of a servant; secondly, that he justified us by his obedience to the Father; and, accordingly that he does not perform this for us in respect of his divine nature, but according to the nature of the dispensation laid upon him. For though God alone is the fountain of righteousness, and the only way in which we are righteous is by participation with him, yet, as by our unhappy revolt we are alienated from his righteousness, it is necessary to descend to this lower remedy, that Christ may justify us by the power of his death and resurrection.

9. If he objects that this work by its excellence transcends human, and therefore can only be ascribed to the divine nature; I concede the former point, but maintain, that on the latter he is ignorantly deluded. For although Christ could neither purify our souls by his own blood, nor appease the Father by his sacrifice, nor acquit us from the charge of guilt, nor, in short, perform the office of priest, unless he had been very God, because no human ability was equal to such a burden, it is however certain, that he performed all these things in his human nature. If it is asked, in what way we are justified? Paul answers, by the obedience of Christ. Did he obey in any other way than by assuming the form of a servant? We infer, therefore, that righteousness was manifested to us in his flesh. In like manner, in another passage, (which I greatly wonder that Osiander does not blush repeatedly to quote,) he places the fountain of righteousness entirely in the incarnation of Christ, “He has made him to be sin for us who knew no sin, that we might be made the righteousness of God in him,” (2 Cor. 5: 21.) Osiander in turgid sentences lays hold of the expression, righteousness of God, and shouts victory! as if he had proved it to be his own phantom of essential righteousness, though the words have a very different meaning, viz., that we are justified through the expiation made by Christ. That the righteousness of God is used for the righteousness which is approved by God, should be known to mere tyros, as in John, the praise of God is contrasted with the praise of men, (John 12: 43.) I know that by the righteousness of God is sometimes meant that of which God is the author, and which he bestows upon us; but that here the only thing meant is, that being supported by the expiation of Christ, we are able to stand at the tribunal of God, sound readers perceive without any observation of mine. The word is not of so much importance, provided Osiander agrees with us in this, that we are justified by Christ in respect he was made an expiatory victim for us. This he could not be in his divine nature. For which reason also, when Christ would seal the righteousness and salvation which he brought to us, he holds forth the sure pledge of it in his flesh. He indeed calls himself “living bread,” but, in explanation of the mode, adds, “my flesh is meat indeed, and my blood is drink indeed,” (John 6: 55.) The same doctrine is clearly seen in the sacraments; which, though they direct our faith to the whole, not to a part of Christ, yet, at the same time, declare that the materials of righteousness and salvation reside in his flesh; not that the mere man of himself justifies or quickens, but that God was pleased, by means of a Mediator, to manifest his own hidden and incomprehensible nature. Hence I often repeat, that Christ has been in a manner set before us as a fountain, whence we may draw what would otherwise lie without use in that deep and hidden abyss which streams forth to us in the person of the Mediator. In this way, and in this meaning, I deny not that Christ, as he is God and man, justifies us; that this work is common also to the Father and the Holy Spirit; in fine, that the righteousness of which God makes us partakers is the eternal righteousness of the eternal God, provided effect is given to the clear and valid reasons to which I have adverted.

10. Moreover, lest by his cavils he deceive the unwary, I acknowledge that we are devoid of this incomparable gift until Christ become ours. Therefore, to that union of the head and members, the residence of Christ in our hearts, in fine, the mystical union, we assign the highest rank, Christ when he becomes ours making us partners with him in the gifts with which he was endued. Hence we do not view him as at a distance and without us, but as we have put him on, and been ingrafted into his body, he deigns to make us one with himself, and, therefore, we glory in having a fellowship of righteousness with him. This disposes of Osiander’s calumny, that we regard faith as righteousness; as if we were robbing Christ of his rights when we say, that, destitute in ourselves, we draw near to him by faith, to make way for his grace, that he alone may fill us. But Osiander, spurning this spiritual union, insists on a gross mixture of Christ with believers; and, accordingly, to excite prejudice, gives the name of Zwinglians to all who subscribe not to his fanatical heresy of essential righteousness, because they do not hold that, in the supper, Christ is eaten substantially. For my part, I count it the highest honor to be thus assailed by a haughty man, devoted to his own impostures; though he assails not me only, but writers of known reputation throughout the world, and whom it became him modestly to venerate. This, however, does not concern me, as I plead not my own cause, and plead the more sincerely that I am free from every sinister feeling. In insisting so vehemently on essential righteousness, and an essential inhabitation of Christ within us, his meaning is, first, that God by a gross mixture transfuses himself into us, as he pretends that there is a carnal eating in the supper; And, secondly that by instilling his own righteousness into us, he makes us really righteous with himself since, according to him, this righteousness is as well God himself as the probity, or holiness, or integrity of God. I will not spend much time in disposing of the passages of Scripture which he adduces, and which, though used in reference to the heavenly life, he wrests to our present state. Peter says, that through the knowledge of Christ “are given unto us exceeding great and precious promises, that by them ye might be partakers of the divine nature,” (2 Pet. 1: 4;) as if we now were what the gospel promises we shall be at the final advent of Christ; nay, John reminds us, that “when he shall appear we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is”, (1 John 3: 2.) I only wished to give my readers a slender specimen of Osiander, it being my intention to decline the discussion of his frivolities, not because there is any difficulty in disposing of them, but because I am unwilling to annoy the reader with superfluous labour.

11. But more poison lurks in the second branch, when he says that we are righteous together with God. I think I have already sufficiently proved, that although the dogma were not so pestiferous, yet because it is frigid and jejune, and falls by its own vanity, it must justly be disrelished by all sound and pious readers. But it is impossible to tolerate the impiety which, under the pretence of a twofold righteousness, undermines our assurance of salvation, and hurrying us into the clouds, tries to prevent us from embracing the gift of expiation in faith, and invoking God with quiet minds. Osiander derides us for teaching, that to be justified is a forensic term, because it behaves us to be in reality just: there is nothing also to which he is more opposed than the idea of our being justified by a free imputation. Say, then, if God does not justify us by acquitting and pardoning, what does Paul mean when he says “God was in Christ reconciling the world unto himself, not imputing their trespasses unto them”? “He made him to be sin for us who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in him,” (2 Cor. 5: 19, 21.) Here I learn, first, that those who are reconciled to God are regarded as righteous: then the method is stated, God justifies by pardoning; and hence, in another place, justification is opposed to accusation, (Rom. 8: 33;) this antithesis clearly demonstrating that the mode of expression is derived from forensic use. And, indeed, no man, moderately verdant in the Hebrew tongue, (provided he is also of sedate brain,) is ignorant that this phrase thus took its rise, and thereafter derived its tendency and force. Now, then, when Paul says that David “describeth the blessedness of the man unto whom God imputeth righteousness without works, saying, Blessed are they whose iniquities are forgiven,” (Rom. 4: 6, 7; Ps. 32: 1,) let Osiander say whether this is a complete or only a partial definition. He certainly does not adduce the Psalmist as a witness that pardon of sins is a part of righteousness, or concurs with something else in justifying, but he includes the whole of righteousness in gratuitous forgiveness, declaring those to be blessed “whose iniquities are forgiven, and whose sins are covered,” and “to whom the Lord will not impute sin.” He estimates and judges of his happiness from this that in this way he is righteous not in reality, but by imputation.

Osiander objects that it would be insulting to God, and contrary to his nature, to justify those who still remain wicked. But it ought to be remembered, as I already observed, that the gift of justification is not separated from regeneration, though the two things are distinct. But as it is too well known by experience, that the remains of sin always exist in the righteous, it is necessary that justification should be something very different from reformation to newness of life. This latter God begins in his elect, and carries on during the whole course of life, gradually and sometimes slowly, so that if placed at his judgment-seat they would always deserve sentence of death. He justifies not partially, but freely, so that they can appear in the heavens as if clothed with the purity of Christ. No portion of righteousness could pacify the conscience. It must be decided that we are pleasing to God, as being without exception righteous in his sight. Hence it follows that the doctrine of justification is perverted and completely overthrown whenever doubt is instilled into the mind, confidence in salvation is shaken, and free and intrepid prayer is retarded; yea, whenever rest and tranquillity with spiritual joy are not established. Hence Paul argues against objectors, that “if the inheritance be of the law, it is no more of promise,” (Gal. 3: 18.) that in this way faith would be made vain; for if respect be had to works it fails, the holiest of men in that case finding nothing in which they can confide. This distinction between justification and regeneration (Osiander confounding the two, calls them a twofold righteousness) is admirably expressed by Paul. Speaking of his real righteousness, or the integrity bestowed upon him, (which Osiander terms his essential righteousness,) he mournfully exclaims, “O wretched man that I am! who shall deliver me from the body of this death?” (Rom. 7: 24;) but retaking himself to the righteousness which is founded solely on the mercy of God, he breaks forth thus magnificently into the language of triumph: “Who shall lay any thing to the charge of God’s elect? It is God that justifieth.” “Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword?” (Rom. 8: 33, 35.) He clearly declares that the only righteousness for him is that which alone suffices for complete salvation in the presence of God, so that that miserable bondage, the consciousness of which made him a little before lament his lot, derogates not from his confidence, and is no obstacle in his way. This diversity is well known, and indeed is familiar to all the saints who groan under the burden of sin, and yet with victorious assurance rise above all fears. Osiander’s objection as to its being inconsistent with the nature of God, falls back upon himself; for though he clothes the saints with a twofold righteousness as with a coat of skins, he is, however, forced to admit, that without forgiveness no man is pleasing to God. If this be so, let him at least admit, that with reference to what is called the proportion of imputation, those are regarded as righteous who are not so in reality. But how far shall the sinner extend this gratuitous acceptance, which is substituted in the room of righteousness? Will it amount to the whole pound, or will it be only an ounce? He will remain in doubt, vibrating to this side and to that, because he will be unable to assume to himself as much righteousness as will be necessary to give confidence. It is well that he who would prescribe a law to God is not the judge in this cause. But this saying will ever stand true, “That thou mightest be justified when thou speakest, and be clear when thou judges,” (Ps. 51: 4.) What arrogance to condemn the Supreme Judge when he acquits freely, and try to prevent the response from taking affect: “I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy.” And yet the intercession of Moses, which God calmed by this answer, was not for pardon to some individual, but to all alike, by wiping away the guilt to which all were liable. And we, indeed, say, that the lost are justified before God by the burial of their sins; for (as he hates sin) he can only love those whom he justifies. But herein is the wondrous method of justification, that, clothed with the righteousness of Christ, they dread not the judgment of which they are worthy, and while they justly condemn themselves, are yet deemed righteous out of themselves.

12. I must admonish the reader carefully to attend to the mystery which he boasts he is unwilling to conceal from them. For after contending with great prolixity that we do not obtain favor with God through the mere imputation of the righteousness of Christ, because (to use his own words) it were impossible for God to hold those as righteous who are not so, he at length concludes that Christ was given to us for righteousness, in respect not of his human, but of his divine nature; and though this can only be found in the person of the Mediator, it is, however, the righteousness not of man, but of God. He does not now twist his rope of two righteousnesses, but plainly deprives the human nature of Christ of the office of justifying. It is worth while to understand what the nature of his argument is. It is said in the same passage that Christ is made unto us wisdom, (1 Cor. 1: 30;) but this is true only of the eternal Word, and, therefore, it is not the man Christ that is made righteousness. I answer, that the only begotten Son of God was indeed his eternal wisdom, but that this title is applied to him by Paul in a different way, viz., because “in him are hid all the treasures of wisdom and righteousness,” (Col. 2: 3.) That, therefore, which he had with the Father he manifested to us; and thus Paul’s expression refers not to the essence of the Son of God, but to our use, and is fitly applied to the human nature of Christ; for although the light shone in darkness before he was clothed with flesh, yet he was a hidden light until he appeared in human nature as the Sun of Righteousness, and hence he calls himself the light of the world. It is also foolishly objected by Osiander, that justifying far transcends the power both of men and angels, since it depends not on the dignity of any creature, but on the ordination of God. Were angels to attempt to give satisfaction to God, they could have no success, because they are not appointed for this purpose, it being the peculiar office of Christ, who “has redeemed us from the curse of the law, being made a curse for us,” (Gal. 3: 13.) Those who deny that Christ is our righteousness, in respect of his divine nature, are wickedly charged by Osiander with leaving only a part of Christ, and (what is worse) with making two Gods; because, while admitting that God dwells in us, they still insist that we are not justified by the righteousness of God. For though we call Christ the author of life, inasmuch as he endured death that he might destroy him who had the power of death, (Heb. 2: 14,) we do not thereby rob him of this honor, in his whole character as God manifested in the flesh. We only make a distinction as to the manner in which the righteousness of God comes to us, and is enjoyed by us, – a matter as to which Osiander shamefully erred. We deny not that that which was openly exhibited to us in Christ flowed from the secret grace and power of God; nor do we dispute that the righteousness which Christ confers upon us is the righteousness of God, and proceeds from him. What we constantly maintain is, that our righteousness and life are in the death and resurrection of Christ. I say nothing of that absurd accumulation of passages with which without selection or common understanding, he has loaded his readers, in endeavoring to show, that whenever mention is made of righteousness, this essential righteousness of his should be understood; as when David implores help from the righteousness of God. This David does more than a hundred times, and as often Osiander hesitates not to pervert his meaning. Not a whit more solid is his objection, that the name of righteousness is rightly and properly applied to that by which we are moved to act aright, but that it is God only that worketh in us both to will and to do, (Phil. 2: 13.) For we deny not that God by his Spirit forms us anew to holiness and righteousness of life; but we must first see whether he does this of himself, immediately, or by the hand of his Son, with whom he has deposited all the fulness of the Holy Spirit, that out of his own abundance he may supply the wants of his members. When, although righteousness comes to us from the secret fountain of the Godhead, it does not follow that Christ, who sanctified himself in the flesh on our account, is our righteousness in respect of his divine nature, (John 17: 19.) Not less frivolous is his observation, that the righteousness with which Christ himself was righteous was divine; for had not the will of the Father impelled him, he could not have fulfilled the office assigned him. For although it has been elsewhere said that all the merits of Christ flow from the mere good pleasure of God, this gives no countenance to the phantom by which Osiander fascinates both his own eyes and those of the simple. For who will allow him to infer, that because God is the source and commencement of our righteousness, we are essentially righteous, and the essence of the divine righteousness dwells in us? In redeeming us, says Isaiah, “he (God) put on righteousness as a breastplate, and an helmet of salvation upon his head,” (Isaiah 59: 17,) was this to deprive Christ of the armour which he had given him, and prevent him from being a perfect Redeemer? All that the Prophet meant was, that God borrowed nothing from an external quarter, that in redeeming us he received no external aid. The same thing is briefly expressed by Paul in different terms, when he says that God set him forth “to declare his righteousness for the remission of sins.” This is not the least repugnant to his doctrine: in another place, that “by the obedience of one shall many be made righteous,” (Rom. 5: 19.) In short, every one who, by the entanglement of a twofold righteousness, prevents miserable souls from resting entirely on the mere mercy of God, mocks Christ by putting on him a crown of plaited thorns.

13. But since a great part of mankind imagine a righteousness compounded of faith and works let us here show that there is so wide a difference between justification by faith and by works, that the establishment of the one necessarily overthrows the other. The Apostle says, “Yea doubtless, and I count all things but loss for the excellency of the knowledge of Christ Jesus my Lord: for whom I have suffered the loss of all things, and do count them but dung, that I may win Christ, and be found in him, not having mine own righteousness, which is of the law, but that which is through the faith of Christ, the righteousness which is of God by faith,” (Phil. 3: 8, 9.) You here see a comparison of contraries, and an intimation that every one who would obtain the righteousness of Christ must renounce his own. Hence he elsewhere declares the cause of the rejection of the Jews to have been, that “they being ignorant of God’s righteousness, and going about to establish their own righteousness, have not submitted themselves unto the righteousness of God,” (Rom. 10: 3.) If we destroy the righteousness of God by establishing our own righteousness, then, in order to obtain his righteousness, our own must be entirely abandoned. This also he shows, when he declares that boasting is not excluded by the Law, but by faith, (Rom. 3: 27.) Hence it follows, that so long as the minutes portion of our own righteousness remains, we have still some ground for boasting. Now if faith utterly excludes boasting, the righteousness of works cannot in any way be associated with the righteousness of faith. This meaning is so clearly expressed in the fourth chapter to the Romans as to leave no room for cavil or evasion. “If Abraham were justified by works he has whereof to glory;” and then it is added, “but not before God,” (Rom. 4: 2.) The conclusion, therefore, is, that he was not justified by works. He then employs another argument from contraries, viz., when reward is paid to works, it is done of debt, not of grace; but the righteousness of faith is of grace: therefore it is not of the merit of works. Away, then, with the dream of those who invent a righteousness compounded of faith and works, (see Calvin. ad Concilium Tridentinum.)

14. The Sophists, who delight in sporting with Scripture and in empty cavils, think they have a subtle evasion when they expound works to mean, such as unregenerated men do literally, and by the effect of free will, without the grace of Christ, and deny that these have any reference to spiritual works. Thus according to them, man is justified by faith as well as by works, provided these are not his own works, but gifts of Christ and fruits of regeneration; Paul’s only object in so expressing himself being to convince the Jews, that in trusting to their ohm strength they foolishly arrogated righteousness to themselves, whereas it is bestowed upon us by the Spirit of Christ alone, and not by studied efforts of our own nature. But they observe not that in the antithesis between Legal and Gospel righteousness, which Paul elsewhere introduces, all kinds of works, with whatever name adorned, are excluded, (Gal. 3: 11, 12.) For he says that the righteousness of the Law consists in obtaining salvation by doing what the Law requires, but that the righteousness of faith consists in believing that Christ died and rose again, (Rom. 10: 5-9.) Moreover, we shall afterwards see, at the proper place, that the blessings of sanctification and justification, which we derive from Christ, are different. Hence it follows, that not even spiritual works are taken into account when the power of justifying is ascribed to faith. And, indeed, the passage above quoted, in which Paul declares that Abraham had no ground of glorying before God, because he was not justified by works, ought not to be confined to a literal and external form of virtue, or to the effort of free will. The meaning is, that though the life of the Patriarch had been spiritual and almost angelic, yet he could not by the merit of works have procured justification before God.

15. The Schoolmen treat the matter somewhat more grossly by mingling their preparations with it; and yet the others instill into the simple and unwary a no less pernicious dogma, when, under cover of the Spirit and grace, they hide the divine mercy, which alone can give peace to the trembling soul. We, indeed, hold with Paul, that those who fulfill the Law are justified by God, but because we are all far from observing the Law, we infer that the works which should be most effectual to justification are of no avail to us, because we are destitute of them. In regard to vulgar Papists or Schoolmen, they are here doubly wrong, both in calling faith assurance of conscience while waiting to receive from God the reward of merits, and in interpreting divine grace to mean not the imputation of gratuitous righteousness, but the assistance of the Spirit in the study of holiness. They quote from an Apostle: “He that comes to God must believe that he is, and that he is the rewarder of them that diligently seek him,” (Heb. 11: 6.) But they observe not what the method of seeking is. Then in regard to the term grace, it is plain from their writings that they labour under a delusion. For Lombard holds that justification is given to us by Christ in two ways. “First,” says he, (Lombard, Sent. Lib. 3, Dist. 16, c. 11,) “the death of Christ justifies us when by means of it the love by which we are made righteous is excited in our hearts; and, secondly, when by means of it sin is extinguished, sin by which the devil held us captive, but by which he cannot now procure our condemnation.” You see here that the chief office of divine grace in our justification he considers to be its directing us to good works by the agency of the Holy Spirit. He intended, no doubt, to follow the opinion of Augustine, but he follows it at a distance, and even wanders far from a true imitation of him both obscuring what was clearly stated by Augustine, and making what in him was less pure more corrupt. The Schools have always gone from worse to worse, until at length, in their downward path, they have degenerated into a kind of Pelagianism. Even the sentiment of Augustine, or at least his mode of expressing it, cannot be entirely approved of. For although he is admirable in stripping man of all merit of righteousness, and transferring the whole praise of it to God, yet he classes the grace by which we are regenerated to newness of life under the head of sanctification.

16. Scripture, when it treats of justification by faith, leads us in a very different direction. Turning away our view from our own works, it bids us look only to the mercy of God and the perfection of Christ. The order of justification which it sets before us is this: first, God of his mere gratuitous goodness is pleased to embrace the sinner, in whom he sees nothing that can move him to mercy but wretchedness, because he sees him altogether naked and destitute of good works. He, therefore, seeks the cause of kindness in himself, that thus he may affect the sinner by a sense of his goodness, and induce him, in distrust of his own works, to cast himself entirely upon his mercy for salvation. This is the meaning of faith by which the sinner comes into the possession of salvation, when, according to the doctrine of the Gospel, he perceives that he is reconciled by God; when, by the intercession of Christ, he obtains the pardon of his sins, and is justified; and, though renewed by the Spirit of God, considers that, instead of leaning on his own works, he must look solely to the righteousness which is treasured up for him in Christ. When these things are weighed separately, they will clearly explain our view, though they may be arranged in a better order than that in which they are here presented. But it is of little consequence, provided they are so connected with each other as to give us a full exposition and solid confirmation of the whole subject.

17. Here it is proper to remember the relation which we previously established between faith and the Gospel; faith being said to justify because it receives and embraces the righteousness offered in the Gospel. By the very fact of its being said to be offered by the Gospel, all consideration of works is excluded. This Paul repeatedly declares, and in two passages, in particular, most clearly demonstrates. In the Epistle to the Romans, comparing the Law and the Gospel, he says, “Moses describeth the righteousness which is of the law, That the man which does those things shall live by them. But the righteousness which is of faith speaketh on this wise, – If thou shalt confess with thy mouth the Lord Jesus, and shalt believe in thine heart that God has raised him from the dead, thou shalt be saved,” (Rom. 10: 5, 6: 9.) Do you see how he makes the distinction between the Law and the Gospel to be, that the former gives justification to works, whereas the latter bestows it freely without any help from works? This is a notable passage, and may free us from many difficulties if we understand that the justification which is given us by the Gospel is free from any terms of Law. It is for this reason he more than once places the promise in diametrical opposition to the Law. “If the inheritance be of the law, it is no more of promise,” (Gal. 3: 18.) Expressions of similar import occur in the same chapter. Undoubtedly the Law also has its promises; and, therefore, between them and the Gospel promises there must be some distinction and difference, unless we are to hold that the comparison is inept. And in what can the difference consist unless in this that the promises of the Gospel are gratuitous, and founded on the mere mercy of God, whereas the promises of the Law depend on the condition of works? But let no pester here allege that only the righteousness which men would obtrude upon God of their own strength and free will is repudiated; since Paul declares, without exceptions that the Law gained nothing by its commands, being such as none, not only of mankind in general, but none even of the most perfect, are able to fulfill. Love assuredly is the chief commandment in the Law, and since the Spirit of God trains us to love, it cannot but be a cause of righteousness in us, though that righteousness even in the saints is defective, and therefore of no value as a ground of merit.

18. The second passage is, “That no man is justified by the law in the sight of God, it is evident: for, The just shall live by faith. And the law is not of faith: but, The man that does them shall live in them,” (Gal. 3: 11, 12; Hab. 2: 4.) How could the argument hold unless it be true that works are not to be taken into account, but are to be altogether separated? The Law, he says, is different from faith. Why? Because to obtain justification by it, works are required; and hence it follows, that to obtain justification by the Gospel they are not required. From this statement, it appears that those who are justified by faith are justified independent of, nay, in the absence of, the merit of works, because faith receives that righteousness which the Gospel bestows. But the Gospel differs from the Law in this, that it does not confine justification to works, but places it entirely in the mercy of God. In like manner, Paul contends, in the Epistle to the Romans, that Abraham had no ground of glorying, because faith was imputed to him for righteousness, (Rom. 4: 2;) and he adds in confirmation, that the proper place for justification by faith is where there are no works to which reward is due. “To him that worketh is the reward not reckoned of grace, but of debt.” What is given to faith is gratuitous, this being the force of the meaning of the words which he there employs. Shortly after he adds, “Therefore it is of faith, that it might be by grace,” (Rom. 4: 16;) and hence infers that the inheritance is gratuitous because it is procured by faith. How so but just because faiths without the aid of works leans entirely on the mercy of God? And in the same sense, doubtless, he elsewhere teaches, that the righteousness of God without the Law was manifested, being witnessed by the Law and the Prophets, (Rom. 3: 21;) for excluding the Law, he declares that it is not aided by worlds, that we do not obtain it by working, but are destitute when we draw near to receive it.

19. The reader now perceives with what fairness the Sophists of the present day cavil at our doctrine, when we say that a man is justified by faith alone, (Rom. 4: 2.) They dare not deny that he is justified by faith, seeing Scripture so often declares it; but as the word alone is nowhere expressly used they will not tolerate its being added. Is it so? What answer, then will they give to the words of Paul, when he contends that righteousness is not of faith unless it be gratuitous? How can it be gratuitous, and yet by works? By what cavils, moreover, will they evade his declaration in another place, that in the Gospel the righteousness of God is manifested? (Rom. 1: 17.) If righteousness is manifested in the Gospel, it is certainly not a partial or mutilated, but a full and perfect righteousness. The Law, therefore, has no part in its and their objection to the exclusive word alone is not only unfounded, but is obviously absurd. Does he not plainly enough attribute everything to faith alone when he disconnects it with works? What I would ask, is meant by the expressions, “The righteousness of God without the law is manifested;” “Being justified freely by his grace;” “Justified by faith without the deeds of the law?” (Rom. 3: 21, 24, 28.) Here they have an ingenious subterfuge, one which, though not of their own devising but taken from Origin and some ancient writers, is most childish. They pretend that the works excluded are ceremonial, not moral works. Such profit do they make by their constant wrangling, that they possess not even the first elements of logic. Do they think the Apostle was raving when he produced, in proof of his doctrine, these passages? “The man that does them shall live in them,” (Gal. 3: 12.) “Cursed is every one that continueth not in all things that are written in the book of the law to do them,” (Gal. 3: 10.) Unless they are themselves raving, they will not say that life was promised to the observers of ceremonies, and the curse denounced only against the transgressors of them. If these passages are to be understood of the Moral Law, there cannot be a doubt that moral works also are excluded from the power of justifying. To the same effect are the arguments which he employs. “By the deeds of the law there shall no flesh be justified in his sight: for by the law is the knowledge of sin,” (Rom. 3: 20.) “The law worketh wrath,” (Rom. 4: 15,) and therefore not righteousness. “The law cannot pacify the conscience,” and therefore cannot confer righteousness. “Faith is imputed for righteousness,” and therefore righteousness is not the reward of works, but is given without being due. Because “we are justified by faith,” boasting is excluded. “Had there been a law given which could have given life, verily righteousness should have been by the law. But the Scripture has concluded all under sin, that the promise by faith of Jesus Christ might be given to them that believe,” (Gal. 3: 21, 22.) Let them maintain, if they dare, that these things apply to ceremonies, and not to morals, and the very children will laugh at their effrontery. The true conclusion, therefore, is, that the whole Law is spoken of when the power of justifying is denied to it.

20. Should any one wonder why the Apostle, not contented with having named works, employs this addition, the explanation is easy. However highly works may be estimated, they have their whole value more from the approbation of God than from their own dignity. For who will presume to plume himself before God on the righteousness of works, unless in so far as He approves of them? Who will presume to demand of Him a reward except in so far as He has promised it? It is owing entirely to the goodness of God that works are deemed worthy of the honor and reward of righteousness; and, therefore, their whole value consists in this, that by means of them we endeavor to manifest obedience to God. Wherefore, in another passage, the Apostle, to prove that Abraham could not be justified by works, declares, “that the covenant, that was confirmed before of God in Christ, the law, which was four hundred and thirty years after, cannot disannul, that it should make the promise of none effect,” (Gal. 3: 17.) The unskillful would ridicule the argument that there could be righteous works before the promulgation of the Law, but the Apostle, knowing that works could derive this value solely from the testimony and honor conferred on them by God, takes it for granted that, previous to the Law, they had no power of justifying. We see why he expressly terms them works of Law when he would deny the power of justifying to theme viz., because it was only with regard to such works that a question could be raised; although he sometimes, without addition, excepts all kinds of works whatever, as when on the testimony of David he speaks of the man to whom the Lord imputeth righteousness without works, (Rom. 4: 5, 6.) No cavils, therefore, can enable them to prove that the exclusion of works is not general. In vain do they lay hold of the frivolous subtilty, that the faith alone, by which we are justified, “worketh by love,” and that love, therefore, is the foundation of justification. We, indeed, acknowledge with Paul, that the only faith which justifies is that which works by love, (Gal. 5: 6;) but love does not give it its justifying power. Nay, its only means of justifying consists in its bringing us into communication with the righteousness of Christ. Otherwise the whole argument, on which the Apostle insists with so much earnestness, would fall. to him that worketh is the reward not reckoned of grace, but of debt. But to him that worketh not, but believeth on him that justifieth the ungodly, his faith is counted for righteousness.” Could he express more clearly than in this word, that there is justification in faith only where there are no works to which reward is due, and that faith is imputed for righteousness only when righteousness is conferred freely without merit?

21. Let us now consider the truth of what was said in the definition, viz., that justification by faith is reconciliation with God, and that this consists solely in the remission of sins. We must always return to the axioms that the wrath of God lies upon all men so long as they continue sinners. This is elegantly expressed by Isaiah in these words: “Behold, the Lord’s hand is not shortened, that it cannot save; neither his ear heavy, that it cannot hear: but your iniquities have separated between you and your God, and your sins have hid his face from you, that he will not hear,” (Isaiah 59: 1, 2.) We are here told that sin is a separation between God and man; that His countenance is turned away from the sinner; and that it cannot be otherwise, since, to have any intercourse with sin is repugnant to his righteousness. Hence the Apostle shows that man is at enmity with God until he is restored to favour by Christ, (Rom. 5: 8-l0.) When the Lord, therefore, admits him to union, he is said to justify him, because he can neither receive him into favor, nor unite him to himself, without changing his condition from that of a sinner into that of a righteous man. We adds that this is done by remission of sins. For if those whom the Lord has reconciled to himself are estimated by works, they will still prove to be in reality sinners, while they ought to be pure and free from sin. It is evident therefore, that the only way in which those whom God embraces are made righteous, is by having their pollutions wiped away by the remission of sins, so that this justification may be termed in one word the remission of sins.

22. Both of these become perfectly clear from the words of Paul: “God was in Christ reconciling the world unto himself, not imputing their trespasses unto them; and has committed unto us the word of reconciliation.” He then subjoins the sum of his embassy: “He has made him to be sin for us who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in him,” (2 Cor. 5: l9-21.) He here uses righteousness and reconciliation indiscriminately, to make us understand that the one includes the other. The mode of obtaining this righteousness he explains to be, that our sins are not imputed to us. Wherefore, you cannot henceforth doubt how God justifies us when you hear that he reconciles us to himself by not imputing our faults. In the same manner, in the Epistle to the Romans, he proves, by the testimony of David, that righteousness is imputed without works, because he declares the man to be blessed “whose transgression is forgiven, whose sin is covered,” and “unto whom the Lord imputeth not iniquity,” (Rom. 4: 6; Ps. 32: 1, 2.) There he undoubtedly uses blessedness for righteousness; and as he declares that it consists in forgiveness of sins, there is no reason why we should define it otherwise. Accordingly, Zacharias, the father of John the Baptist, sings that the knowledge of salvation consists in the forgiveness of sins, (Luke 1: 77.) The same course was followed by Paul when, in addressing the people of Antioch, he gave them a summary of salvation. Luke states that he concluded in this way: “Through this man is preached unto you the forgiveness of sins, and by him all that believe are justified from all things from which ye could not be justified by the law of Moses,” (Acts 12: 38, 39.) Thus the Apostle connects forgiveness of sins with justification in such a way as to show that they are altogether the same; and hence he properly argues that justification, which we owe to the indulgence of God, is gratuitous. Nor should it seem an unusual mode of expression to say that believers are justified before God not by works, but by gratuitous acceptance, seeing it is frequently used in Scripture, and sometimes also by ancient writers. Thus Augustine says: “The righteousness of the saints in this world consists more in the forgiveness of sins than the perfection of virtue,” (August. de Civitate Dei, lib. 19, cap. 27.) To this corresponds the well-known sentiment of Bernard: “Not to sin is the righteousness of God, but the righteousness of man is the indulgence of God,” (Bernard, Serm. 22, 23 in Cant.) He previously asserts that Christ is our righteousness in absolution, and, therefore, that those only are just who have obtained pardon through mercy.

23. Hence also it is proved, that it is entirely by the intervention of Christ’s righteousness that we obtain justification before God. This is equivalent to saying that man is not just in himself, but that the righteousness of Christ is communicated to him by imputation, while he is strictly deserving of punishment. Thus vanishes the absurd dogma, that man is justified by faith, inasmuch as it brings him under the influence of the Spirit of God by whom he is rendered righteous. This is so repugnant to the above doctrine that it never can be reconciled with it. There can be no doubt that he who is taught to seek righteousness out of himself does not previously possess it in himself. This is most clearly declared by the Apostle, when he says, that he who knew no sin was made an expiatory victim for sin, that we might be made the righteousness of God in him (2 Cor. 5: 21.) You see that our righteousness is not in ourselves, but in Christ; that the only way in which we become possessed of it is by being made partakers with Christ, since with him we possess all riches. There is nothing repugnant to this in what he elsewhere says: “God sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh, and for sin condemned sin in the flesh: that the righteousness of the law might be fulfilled in us,” (Rom. 8: 3, 4.) Here the only fulfillment to which he refers is that which we obtain by imputation. Our Lord Jesus Christ communicates his righteousness to us, and so by some wondrous ways in so far as pertains to the justice of Gods transfuses its power into us. That this was the Apostle’s view is abundantly clear from another sentiment which he had expressed a little before: “As by one man’s disobedience many were made sinners, so by the obedience of one shall many be made righteous,” (Rom. 5: 19.) To declare that we are deemed righteous, solely because the obedience of Christ is imputed to us as if it where our own, is just to place our righteousness in the obedience of Christ. Wherefore, Ambrose appears to me to have most elegantly adverted to the blessing of Jacob as an illustration of this righteousness, when he says that as he who did not merit the birthright in himself personated his brother, put on his garments which gave forth a most pleasant odour, and thus introduced himself to his father that he might receive a blessing to his own advantage, though under the person of another, so we conceal ourselves under the precious purity of Christ, our first-born brother, that we may obtain an attestation of righteousness from the presence of God. The words of Ambrose are, – “Isaac’s smelling the odour of his garments, perhaps means that we are justified not by works, but by faith, since carnal infirmity is an impediment to works, but errors of conduct are covered by the brightness of faith, which merits the pardon of faults,” (Ambrose de Jacobo et Vita Beats, Lib. 2, c. 2.) And so indeed it is; for in order to appear in the presence of God for salvation, we must send forth that fragrant odour, having our vices covered and buried by his perfection.