‘And Nadab and Abihu, the sons of Aaron, took either of them his censer, and put fire therein, and put incense thereon, and offered strange fire before the LORD, which he commanded them not.‘ Leviticus 10:1

Modern Evangelicalism bears little resemblance to the faith of our Puritan and Pilgrim fathers. Our aim is to make people feel better, theirs was to teach them how to worship God. We hear of how God enables people to save themselves, they spoke of the God who saves. Our aim is to evenly distribute honor and praise between man and God, their chief aim was to see that God received all glory. The average modern evangelical believes that revivals come via techniques, our Puritan and Pilgrim fathers believed that revivals were sovereign acts of God. Today, the local church is held in low esteem and evaluated not by the fruit of changed lives but by the standard of numbers: how many buildings, how much money, how many converts.

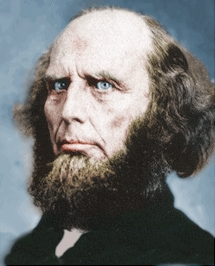

Our forefathers believed that the local church was the most important institution in the community and evaluated it by its faithfulness to God, His Word and His Ways. Today the mind is seen as a hindrance to true spirituality. Jonathan Edwards and the average minister of his day believed the training of the intellect to be of paramount importance, This transformation of mind sets did not happen overnight and cannot be solely attributed to one event or one person. However, it can be said that one man, more than any other, acted as a catalyst and prototype: that man was Charles Grandison Finney (1792-1875.) While practicing law in New York, Finney attended church services conducted by a friend, George Gale. In 1821, he became a Christian and almost immediately declared that he has been retained by God to ‘plead His cause.’ For the next eight years he held revival meetings in the Eastern States. For a short while he was the pastor of Second Presbyterian Church in New York City. However, He withdrew from the presbytery, rejecting the Presbyterian disciplinary system. In 1835 he became a professor in a new Bible college in Oberlin, Ohio, serving as president from 1851-1866. When Finney began his itinerating as a frontier evangelist, his meetings were almost immediately attended with large numbers of conversions, as well as great controversy (Iain H. Murray, Revival & Revivalism: The Making and Marring of American Evangelicalism 1750-1858, [Banner of Truth Trust, 1994] pp. 231-235). The general points of controversy can be seen in the following headings from a Pastoral Letter, drafted by pastors of Congregational churches in Oneida and sent to ministers of the Ministers of the Oneida Association.

‘Condemning in the gross, or approving in the gross; Making too much of any favorable appearance; Not guarding against false conversions; Ostentation and noise; The hasty acknowledgment of persons converted; (The strength of a church does not consist in its numbers, but in it’s graces . . . We fear that desire of counting numbers is too much indulged, even by good people.)’;

‘Suffering the feelings to control judgment; Talking too much about opposition; Censuring, as unconverted, or as cold, stupid, and dead, those who are in good standing in the visible church; Praying for persons by name, in an abusive manner; Denouncing as enemies or reviling those who do not approve of everything that is done; Taking the success of any measures, as an evidence that those measures are right, and approved by God.’ (Murray, p. 234f.)

The problem was not that the concerned pastors did not believe in revival. Their concern was with Finney’s methodology and the fact that the means to attaining a ‘revival’ were being so perverted that the results were not only detrimental to the church but injurious to the glory of God. Up to that time, the majority of ministers attributed revivals to the sovereign act of a merciful God. With the coming of Finney, such beliefs were supplanted. While it is a shock to the majority of modern Christians in America, Calvinism and Reformed Theology were the majority report from the beginning of our nation until the time of Finney. While Whitherpsoon, Edwards and Whitefield taught that God was sovereign in the affairs of humanity, Finney helped propagate the Arminian belief that all was in the hands of the individual. This was especially true regarding revival. For Finney and his followers, revivals came via promotion. As he writes in his Lectures on Revivals of Religion:

‘Revivals were formerly regarded as miracles . . . For a long time it was supposed by the Church that a revival was a miracle, an interposition of Divine power, with which they had nothing to do, and which they had no more agency in producing than they had in producing thunder, or a storm of hail, or an earthquake. It is only within a few years that ministers generally have supposed revivals were to be promoted, by the use of means designed and adapted specially to that object’ (Charles G. Finney, Lectures on Revival [Leavitt, Lord & Co., 1835]. p. 17f)

To the modern ear, Finney sounds quite ‘normal.’ But to the Calvinistic ears of our spiritual forefathers, he was espousing nothing short of heresy. To say that revivals could be planned, promoted and propagated by man necessitated a revamping of one’s appraisal of human nature. If humans are dead in sin, as the apostle Paul writes in his letter to the Ephesians, then regeneration depended upon the sovereign act of the Holy Spirit. However, if regeneration was a matter of a will not enslaved to unrighteousness but free to choose between sin and righteousness, then the individual needed to be argued or persuaded into the Kingdom of God (A great overview of Finney’s theology can be found in Benjamin Warfield’s, Perfectionism, Chapter IV. ‘The Theology of Charles G. Finney.’). One obvious consequence of this reappraisal of human nature is the placing of technique at the forefront of evangelism and revivals. Before Finney, preaching the Word of God and prayer were generally believed to be the means of grace God would use in His sovereign timing, to bring revival. Now, it was a matter of changing people’s minds. Therefore, most anything that could accomplish this end became ‘holy’: anything that was seen to hinder the individual’s decision-making process was either foolish or evil. Did teaching ‘mouldy orthodoxy’ (Henry Ward Beecher) bore people? Then it must be replaced with emotionally challenging storytelling that will move the masses. Does the singing of King David’s Psalms excite the masses? If not, write simple (simplistic?) choruses and put them to popular tunes. Everything the church does must now be evaluated by one thing: results.

This, of course, leads to a reevaluation of the qualification of the minister. In the beginning of our nation’s history, the majority of our spiritual forefathers understood the necessity of education and saw a sound mind as a character quality required by God. The Puritans placed great value on education and were typically the leading educators. As Richard Hofstadter notes,

‘Among the first generation of American Puritans, men of learning were both numerous and honored. There were about one university-trained scholar, usually from Cambridge or Oxford, to every forty of fifty families. Puritans expected their clergy to be distinguished for scholarship, and during the entire colonial period all but five percent of the clergymen of New England Congregational churches had college degrees. These Puritan emigrants, with their reliance upon the Book and their wealth of scholarly leadership, founded that intellectual and scholarly tradition which for three centuries enabled New England to lead the country in educational and scholarly achievements (Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life,’ [Alfred A. Knopf, 1979] p.60).

With Finney and the Second Great Awakening, this testimony to academic and intellectual excellence waned. Because so many of the pastors of ‘dead’ churches (i.e., those who did not attain the desired results) were not ‘converted,’ (i.e., they disagreed with Finney and men of his ilk), a polarization took place between men of the ‘Spirit’ and men of ‘intelligence.’ It increasingly became a badge of honor to be ignorant! To be educated could well be grounds enough to call into question one’s conversion—or at least his sanctification. What the modern minister needed was not so much an education in biblical languages, orthodoxy, history and the like but an understanding of human psychology and the techniques of moving the sinner’s will to choose God. It seems that what God needed was not ministers but salesmen. As Iain Murray writes of this time,

‘In the new age of democracy, now dawning, traditional positions and offices stood for far less, and half-educated, fast-talking speakers, claiming to preach the simple Bible, and attacking the Christian ministry, were more likely then ever to find a hearing . . . . Finney frequently criticized ministers of the gospel: His lectures were full of examples of revivals which had been killed by the inept practices of ministers unskilled in the science of revivalism.’ (Murray, p. 282).

From the Puritan ideal of the minister as an intellectual leader, the church, under men like Finney, began to think of the ideal minister as a crusading exhorter who never moved away from the most simplistic explanations of the faith for fear of ‘quenching the Spirit’ and resisting revival. Finney, like Dwight L. Moody, opposed the formal study of divinity. Quoting Nathan O. Hatch, David Wells notes that ‘Their sermons were colloquial, employing daring pulpit storytelling, no-holds-barred appeals, overt humor, strident attacks, graphic application, and intimate personal experience.’ Charles Finney despised sermons that were formally delivered on the grounds that they put content ahead of communication . . .’ (David Wells, God in the Wasteland: The Reality of Truth in a World of Fading Dreams, [Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1994] p.62).

The church as Mater and Schola was replaced with the church as a revival center. What was all-important to the leaders of the Second Great Awakening was one’s ‘personal salvation.’ Every other concern (e.g., social, intellectual, political) was secondary, if of any importance at all. Subsequently, only those denominations ‘which exploited innovative revival techniques to carry the gospel to the people, flourished’ (Mark Noll, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, [Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1994] p.62).

Finney believed that proof of the truths he was preaching concerning revival was in the great numbers of those being converted. He never wearied of telling his fellow ministers that, if they would just follow his techniques, revival would inevitably follow. However, by Finney’s own admission, rather than a continuous revival sweeping across the land ‘The glory has been departing and revivals have been becoming less and less frequent—less powerful'(Murray, p.285f). Worse, he admits that the great body of those who were thought to have been converted were a ‘disgrace to religion’ (Murray, p.289). By Finney’s own standard, his teachings on how to produce converts and revival, as well as their underlying assumptions, were proven wrong.

Finney’s theology betrayed him. Because he believed that everyone had the ability to instantly receive Christ upon hearing the gospel, many who were spiritually unprepared decided to accept Christ, but in reality were still, at best, seekers. Finneyism, in seeking to close the sale, actually served to close hearts and minds to the biblical message of salvation, leaving people deceived as to their spiritual state, wondering why the Christian life eluded them. Tragically, Finneyan theology is still all the rage in much of Evangelicalism. One can only hope that its defective fruit will plague, burden and shame us to the point where our humiliation will turn to humility which will lead to the pursuit of biblical truth and godly practices.

Copyright 1996 Monte E. Wilson permission to reprint granted as long as full credit and address cited Classical Christianity PO Box 22 Atlanta, GA. 30239